Fritz Macho

Revisited

FOTOHOF>GALLERY opened on 11 June 1981 with an exhibition featuring photographs by Fritz Macho which had only recently been discovered. During the 1930s, Fritz Macho took portraits of “people in the countryside” (also the title of the illustrated book published by Residenz Verlag, now out-of-print). In its foreword, Peter Weiermair compared it with the work of August Sander.

Today, 40 years later, the FOTOHOF>ARCHIVE has produced high-quality digital prints from newly discovered negatives by the photographer. In the current exhibition, a selection of analogue photographs from 1981 is complemented by the digitally processed prints from 2021. These new discoveries consist of private photographs featuring a very idiosyncratic perspective on his family. By the same token, they underscore the photographic style characteristic of Fritz Macho’s work.

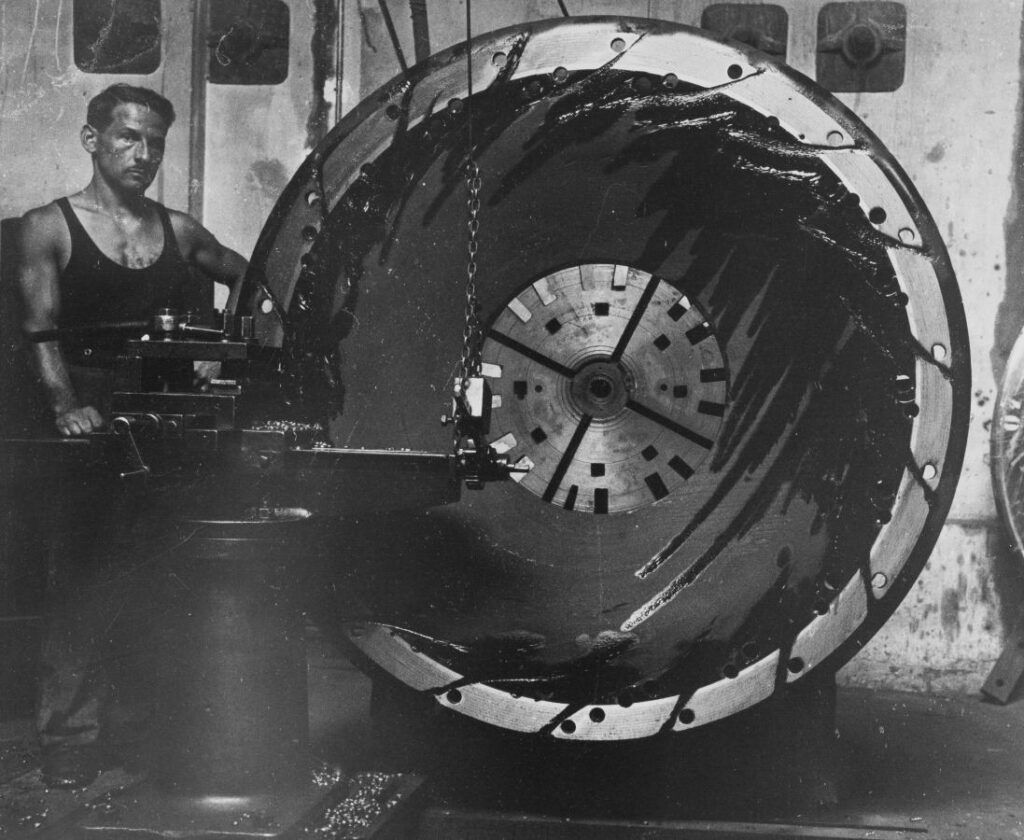

Fritz Macho (1899−1974) came from the small town of Lend in the province of Salzburg and worked as a lathe operator and locksmith at the local aluminium factory. Clearly, he nurtured two passions: hiking in the mountains (as evidenced by a tour book he kept for many decades) and photography. The photographs from his estate were taken in the 1930s, testimonies of a past life that stretches back half a century. Their documentary value is partly attributable to the fact that an amateur photographer was at work here.

Macho photographed the people in his immediate surroundings, and the mutual trust is apparent in the pictures. His excursions up to the alpine pastures above the village of Lend were undoubtedly motivated by his love of hiking; but they were also opportunities to mend various metal implements for the locals, for which he received food in return. Still, he took meticulous care with his photographs and staged those he depicted in their working environment in order to show the everyday reality of their livelihoods while portraying them in ways both self-assured and dignified. The same very much applies to the self-portraits also found in his estate. They, too, reveal him as a self-confident worker and proletarian just as proficient working on his huge lathe as he was playing various musical instruments in his leisure time.

The line that has now been drawn by the exhibition to the newly discovered pictures of his family is entirely congruent with Fritz Macho’s own approach to his protagonists. Far removed from the ever cheerful and smiling poses of contemporary holiday snapshots, he stage-manages his family members in their environment, his daughter first and foremost. As their earnest facial expressions convey, both the photographer and the sitter are fully aware of the situation, namely a picture-taking for the sake of posterity. Like his photographs of “people in the countryside“, he manages to strike the balance between staged photographic situations and the self-determination of his protagonists.