Time and Again

Dasha Karetnikova, Eugenia Maximova, Nastassja Nefjodov, Fungi Phuong Tran Minh

The exhibition “Time & Again” features four autobiographical narratives shaped by political decisions, social power relations, and historical upheavals. Research takes the photographers back to places of their past; they document traces left behind by violence, oppression, and social injustice. The results are multi faceted projects that not only tell personal stories, but also address the consequences of power and systemic violence that have left their traces in private lives. The title “Time & Again” refers to repetitions—in biographies as well as in collective experiences—to returning forms of exploitation and social injustice as well as transgenerational trauma. The works on display are composed like everyday scenes out of a road movie. Showing a seeming return to a normality, which lies like a thin film over past events, which could reoccur at any moment.

Fungi Phuong Tran Minh

In her photo series “Mein ferner Osten” Fungi Phuong Tran Minh embarks on a personal journey to her past: she follows the story of her parents, who came to the German Democratic Republic in the 1980s as Vietnamese contract workers After her father had already been working in a factory in Egeln, she followed him there together with her mother and sister. Shortly afterwards, the GDR collapsed, a political and social upheaval that subsequently confronted the family with racism and exclusion.

Together with her mother, Fungi Phuong Tran Minh travels to the places where the family lived during her childhood and youth. Traces of the past become visible in her photographs: a closed ice cream parlor, an old Trabi, an open construction site. These images not only show the current state of the places, but also provide insight into the photographer‘s inner emotional world. She accompanies these images with texts that, in their clarity, seem to be the counterpoint to the poetic narratives of her photographs. In them, she talks about her ambivalent relationship to concepts such as identity and national belonging: “For me, home sounds like the Vietnamese terms ‘hai mat’ (two faces) or ‘hai mat’ (two eyes) – and that‘s exactly how I am seen or how I see the world.” F. P. T. M.

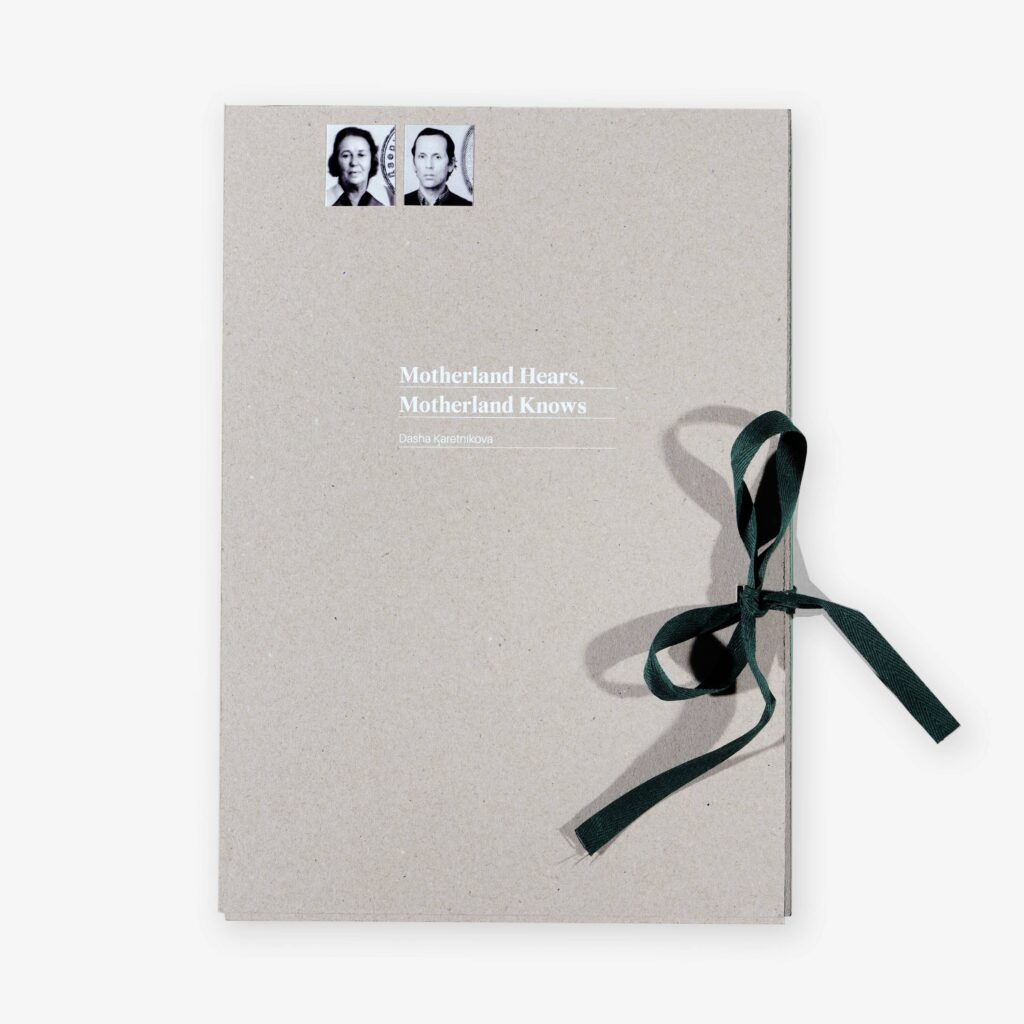

Dasha Karetnikova

The title, “Motherland hears, Motherland knows” refers to the name and opening line of a song Dasha Karetnikova’s father once sang in front of Joseph Stalin as a member of a Soviet boys‘ choir. Her father Georgiy Karetnikov was born in ALZhIR (the Akmolinsk Camp of Wives of Traitors to the Motherland), northern Kazakhstan in 1938. His mother Olga Galperina, was arrested in Moscow while she was pregnant and sent to the camp for 8 years. The children of the prisoners lived in complete isolation, separated from their mothers by barbed wire. Dasha’s father first saw his mother at the age of 8, when they were freed.

“Motherland hears, Motherland knows” combines photographs from Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Russia with a collection of archival materials documenting several trips the artist took with her father between 2019 and 2023. They visited the places where Georgiy Karetnikov lived during and after his imprisonment. Despite lifelong attempts and the intense process of making this project, Dasha’s father died in 2024 without knowing exactly why his mother was arrested so many years ago. After having been born in the Gulag in 1938 and living in the shadows of accusations, he was once again pursued by state authorities in old age in 2022.

This project was made possible with the support of »Artist Solidarity Program Europe« , the Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs of the Republic of Austria and Dialog Büro Vienna. Special thanks to Dr. Helga Rabl-Stadler, Simon Mraz and people whom we cannot name for their safety.

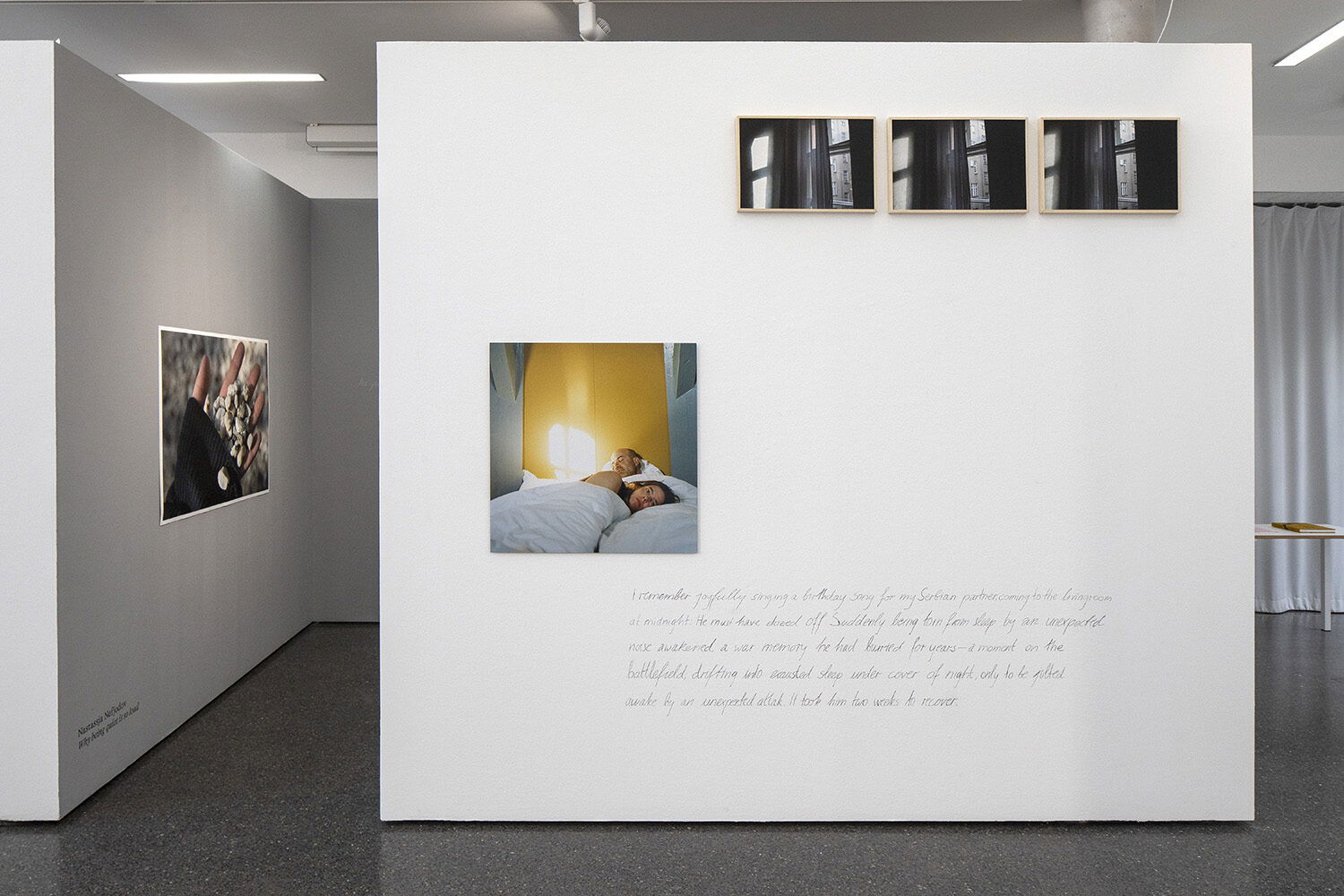

Nastassja Nefjodov

In “Why being quiet is so loud” Nastassja Nefjodov accompanies her partner Partner Dejan during his trauma therapy and records his thoughts, memories, and feelings. On June 30, 1991, Dejan began his military service in the Yugoslav People‘s Army at the age of 19. Shortly thereafter, the conflict in the region escalated into open warfare, and his military service was no longer a preparation for war, but became reality. Traumatized and robbed of his youth, he returned to Belgrade in 1992.

In her work, Nastassja Nefjodov reflects on what it means to share the intimate space with the trauma of a loved one and to use the camera to cover the ensuing distance. For the artist, it is a reflection on a difficult healing process. The film is part of a larger installation with the same title, “Why being quiet is so loud,” which deals with Nastassja Nefjodov‘s family history and the long-lasting effects of war trauma: “My family collects stories of war and I seem to continue to do so as well. I decided to share these vulnerable stories. I believe that this act not only fosters personal healing but also contributes to the healing journeys of others, breaking cycles of pain and violence.” N. N.

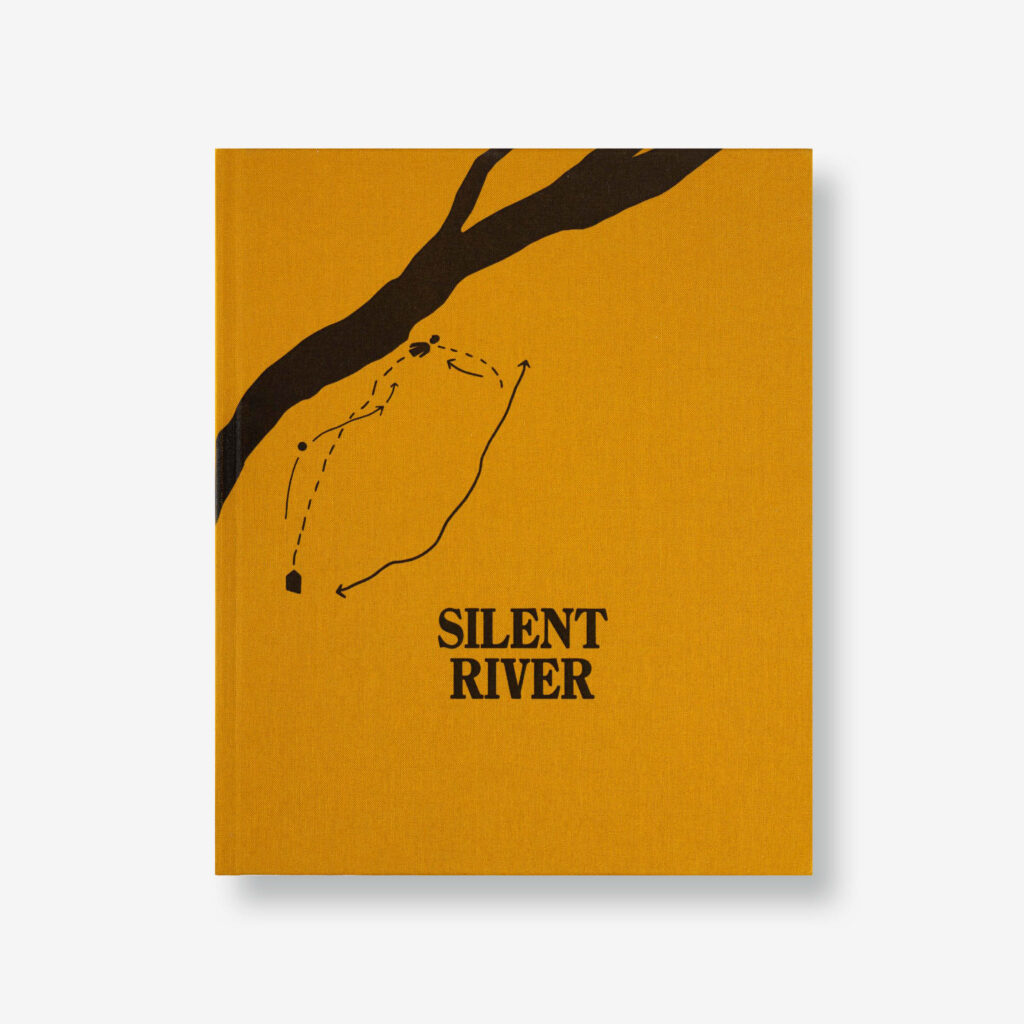

Eugenia Maximova

On October 6, 2018, 30-year-old television journalist Victoria Marinova was brutally raped and murdered in the Bulgarian city of Ruse. At her station, TVN Television, she gave investigative journalists — among others — a platform. Her violent death cast a harsh spotlight not only on widespread corruption in the country, but also on the dangerous conditions faced by journalists reporting on such issues. As media outlets around the world started expressing solidarity, international attention started a conversation about press freedom and journalist safety in Bulgaria. The debate abruptly ended when, after about 48 hours, a 21-year-old man of Roma descent was arrested as the supposed murder. Applying an artistic as well as documentary approach, Vienna-based photographer Eugenia Maximova challenges this convenient silence. In addition, she looks at the emotional repercussions because Maximova is also personally affected: the murdered journalist had been her sister-in-law and friend. “Silent River” thus seeks to raise questions as much as it documents a personal journey of grief and loss, of anger and despair. Eugenia Maximova captures elegiac views of the city, empty spaces, many of which in a desolate state yet not without beauty. The project seeks to map out a subjective topography of the murder in that it follows not one but two trajectories: that of Victoria Marinova and that of her alleged murderer as they both move through the post-Communist cityscape until their paths cross on the banks of the Danube. In doing so, a third trajectory emerges: that of the artist herself.