Raphaël Dallaporta

Domestic Slavery / Antipersonnel

Raphaёl Dallaporta’s photographic work is dedicated to a new form of documentary reportage, with a focus on the social realities and humanitarian abuses of our time. The two series “Antipersonnel” and “Domestic Slavery” can be seen at the FOTOHOF.

Dallaporta sees himself as a contemporary witness who makes the social reality of our society and its grievances visible with his photographic works. He studied at the Paris film and media school “École des Gobelins”. In 2002, he received a one-year residency at the Italian media laboratory “Fabrica”, in Manera near Venice, founded by the Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani. The content-related objective of this private media academy – to devote himself to innovative social issues in connection with economic and social factors – has more than clearly influenced Dallaporta in the development of his personal work.

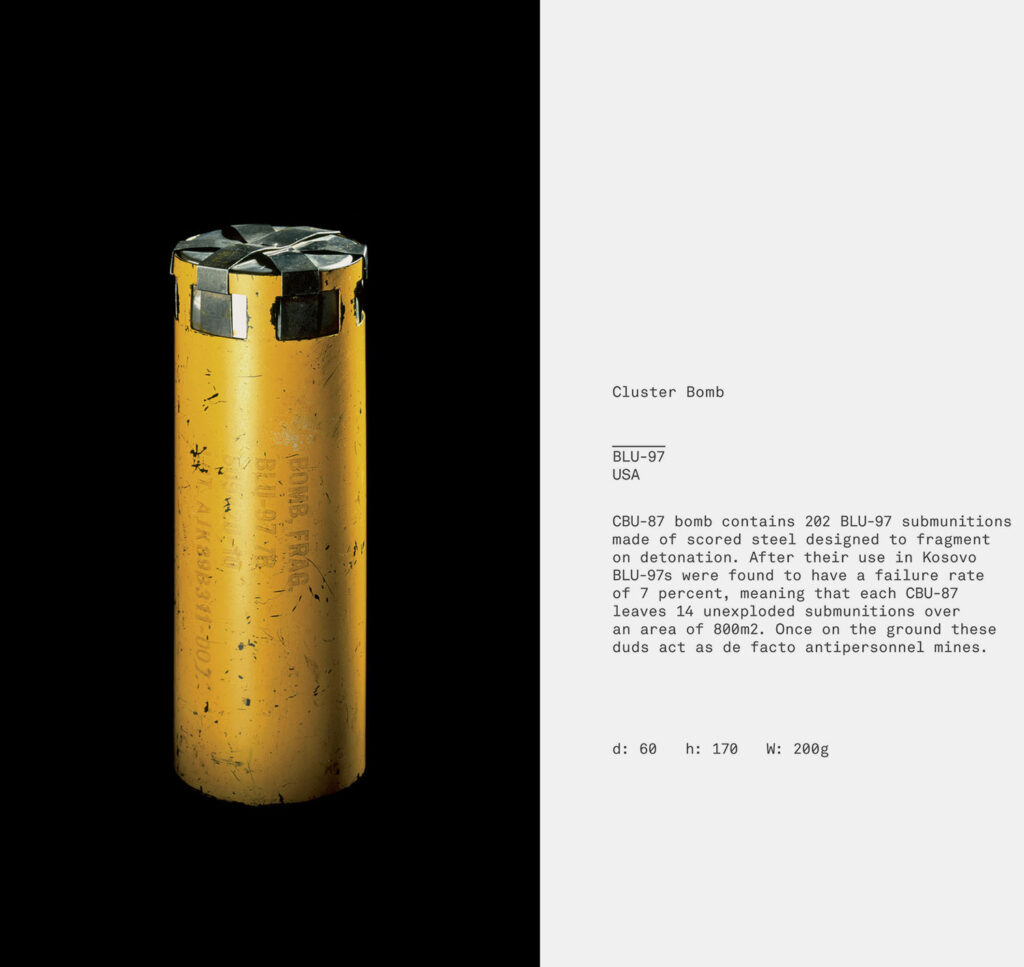

He approaches his issues through lengthy research, and a few years ago he succeeded in gaining recognition, especially with his photo series “Antipersonnel” about landmines and cluster bombs. Through a personal meeting and conversations with mine rooms working in Bosnia in 1998, he began to research this explosive social issue. It took him two years to convince the French military to support him in his project and to give him access to this extraordinary international collection of landmines and cluster bombs.

Dallaporta photographed mines and cluster bombs like stylised pieces of jewellery or perfume bottles in their original size – 1:1 – through the accompanying picture text, these visually seductive photographs arouse fascination and revulsion in equal measure.

“Working with the deminers, has shown me that mines are not only a humanitarian problem, but also a political, economic and environmental one,” says Dallaporta. “So the main problem is the object of the mine itself, which causes many victims.”

His photos do not show emotions, do not act on the emotional level, but rather leave the viewer free and nudge him to think for himself about what is depicted. And in this case, they remind us of this perfidious stock market-supported business model that ultimately still kills or seriously injures thousands of people all over the world.

In “Domestic slavery” Dallaporta looks at forms of modern slavery in France – mostly the fates of African migrants who were kept like serfs for years by French families under inhumane conditions. Dallaporta shows us professional, cool architectural shots that show more or less aesthetic exterior facades of these places. Only through the accompanying text do we learn the facts of his meticulous research on the respective victims, which was done in cooperation with the journalist Ondine Millot, and find out what happened to Elsa, Legba, Aina, Diane, Diouma, Bernadette, Henriette behind these cool facades.

Again, the quiet, calm and seemingly harmless image turns into a disturbing scenario of the cruel treatment of human dignity and leaves us more than thoughtful. Dallaporta does not use the camera to capture an event, his terrain is the aftermath; thus he enters a level of reflection. “I act like a television reporter who goes to the site of a tragic event and produces “human interest” stories – they are at the site, but there is nothing to see!”