Annelies Oberdanner, Ingeborg Strobl

Oberdanner / Strobl

Annelies Oberdanner and Ingeborg Strobl do not regard themselves as photographers in the traditional sense; rather, they are both visual artists with an oeuvre spanning multiple genres. Photography is used time and again in conjunction with other artistic mediums; rarely is the single image conceived without its setting. The auratic singular photograph plays a subordinate role. Both artists have a preference for series: some combined with texts in artist’s books (Oberdanner, Strobl), others associated with sculptures in exhibition installations (Oberdanner).

In terms of content the exhibition at FOTOHOF Salzburg is designed as a dialogue on our perception of the unspectacular, the incidental and the ephemeral. It is an approach founded on both artists’ extensive archives of photographs. Both seem to share a particular attitude towards the world, one which results in contemplative, but also alert and empathetic observation, in common for instance with the “collector” Agnès Varda. In fact, it is no coincidence that Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse is a film both women artists like very much.

Another area of consensus the two artists share in their fundamental approach is a mistrust of strategies of overwhelming, overabundance and breathtaking perfection. Both their idioms are far softer, their visual presence more restrained and unobtrusive – and unfussy. The small format predominates. At no point does the viewer feel harried by the exhibits on show on the gallery’s bright and open premises.

Annelies Oberdanner

Annelies Oberdanner’s contribution to the exhibition consists of a long series of photographs and a group of sculptural objets trouvés. For instance the fragment of cast iron waste pipe with black enamelled inner wall sourced from the grounds of Vienna’s Nordbahnhof railway station, or a green plank of wood found on the Danube Island. For the artist the sculptural quality of these sculptures trouvées stems from their materiality, fully realised by each particular shape. They have come about without concept or, in the case of the large round lichen-speckled stone from a forest in Tyrol, without human contact. The other pieces are coarsely processed (sawn off, broken, discarded, …) and then finely polished by the effect of weathering.

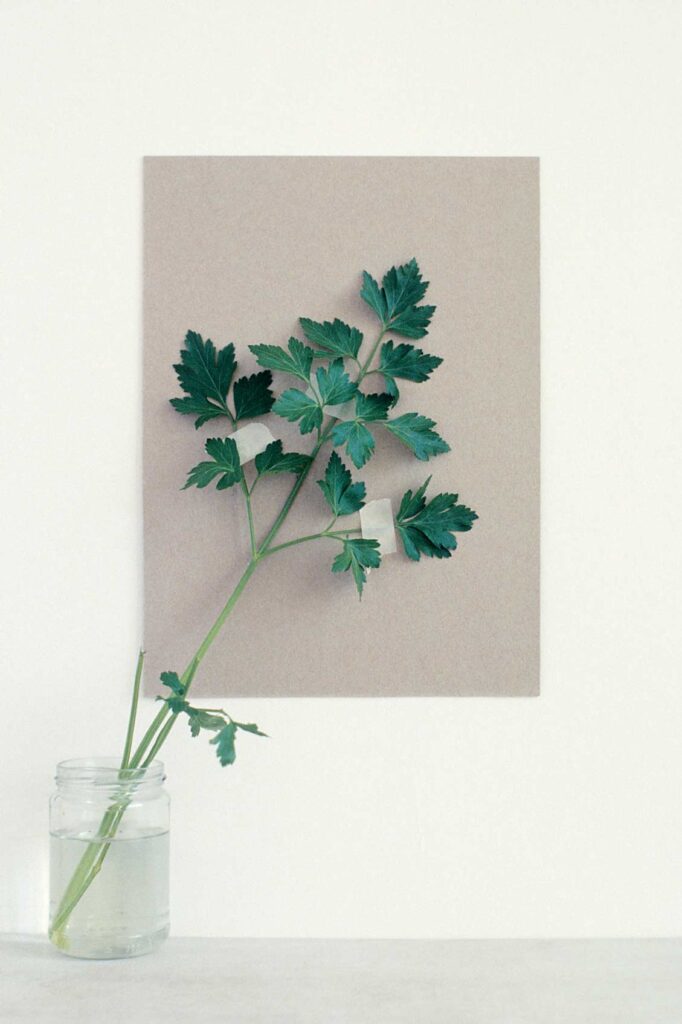

Oberdanner’s photographic work also references the sculptural. Some of the photographs feature the artist’s own objects. Other “random” photographs came out of nowhere, as it were, and have been coupled to this area of personal interest; one might even say they were something of a fetish.

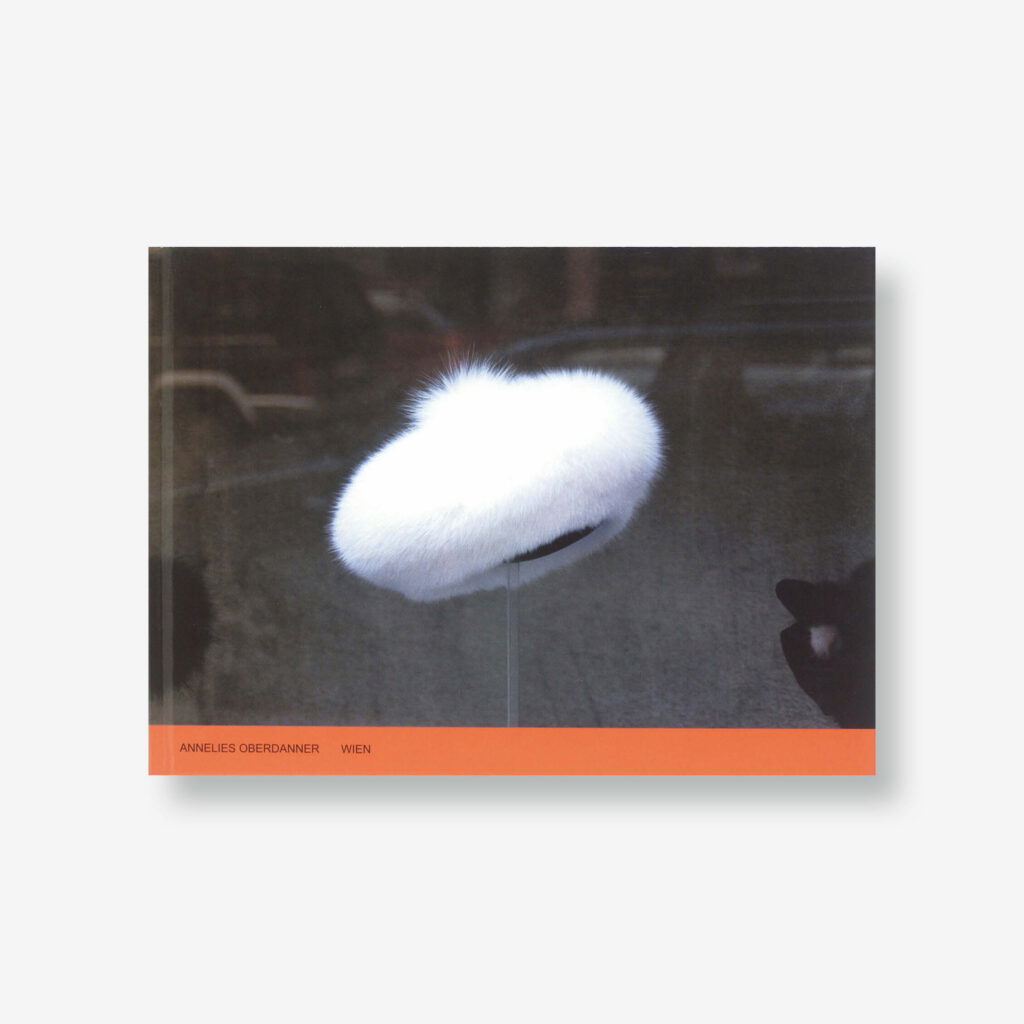

At the exhibition the large 20 x 30 cm prints float unframed in front of the walls, mounted on thin wooden battens. The display window wall for instance shows the following series: a hand twiddling a pair of cherries. The cherries appear almost black as they dangle in the shadow, and their outline (and shape) changes from one photograph to the next. In the fourth photograph the hand has placed them in the sunlight, which suddenly illuminates the crimson colour of the fruit and entirely sidelines its shape.

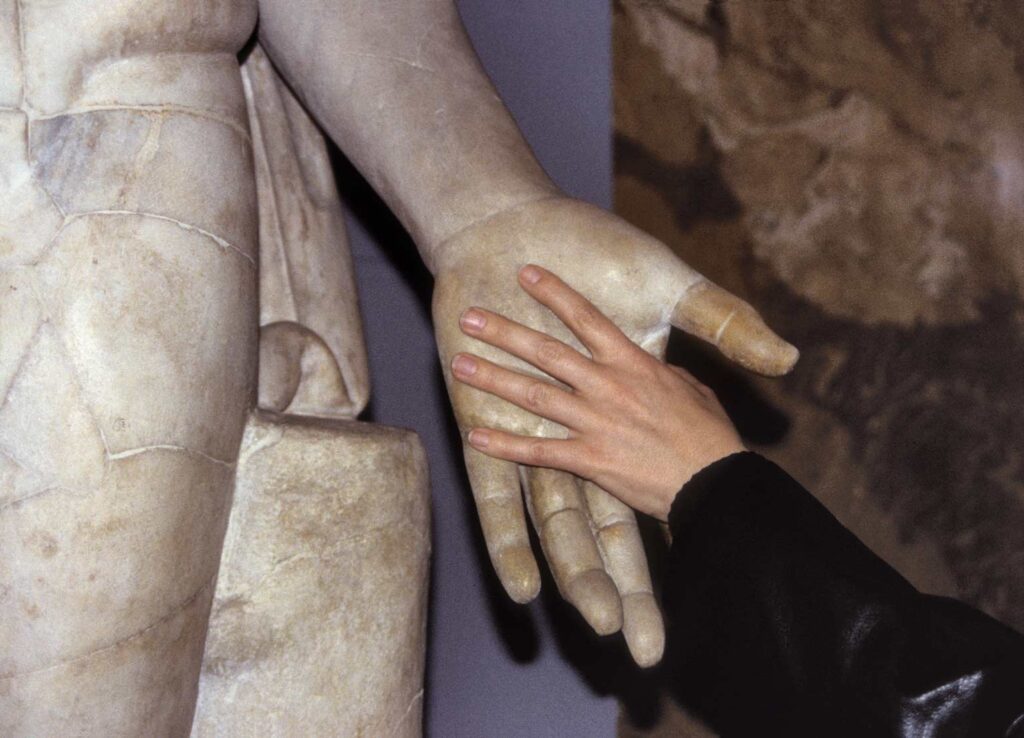

Inside the exhibition space a series comprised of 60 photographs subdivided by motif groups runs along two walls. It begins with five photographs of little piles of snow left over from the winter, sitting like small animals in a field already green. Their crumpled irregularity of surface and shape is picked up by the second motif group (crashed cars and discarded clothes), conveying an entirely different atmosphere leaden with violence. It is followed by several photographs of hands delicately holding vulnerable objects, suggesting pleasantly tactile sensations. This creates a chain of photographs that incrementally shifts the content and meaning of each motif. The longest series in the sequence consists of photographs taken in the artist’s studio over the years, in passing and without purpose. Scratches and specks of dust have impacted the surface of the rolls of film (slides) to a greater or lesser degree (the passage of time thus visible on the prints). Taken as analogue photographs at different times of the day in different light conditions and with different films and cameras, they combine into a photographic studio journal that blends photographs of the artist’s own objects and sculptures with items of everyday life.

Ingeborg Strobl

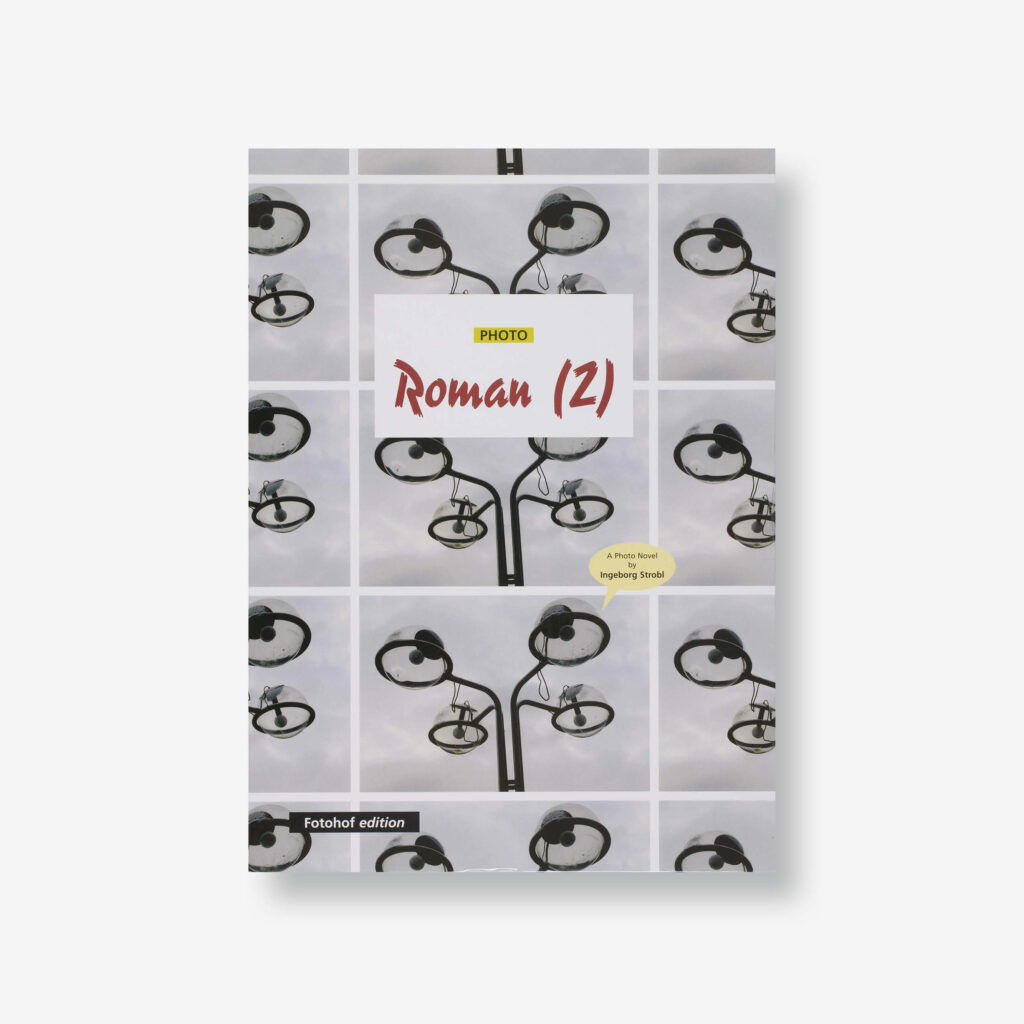

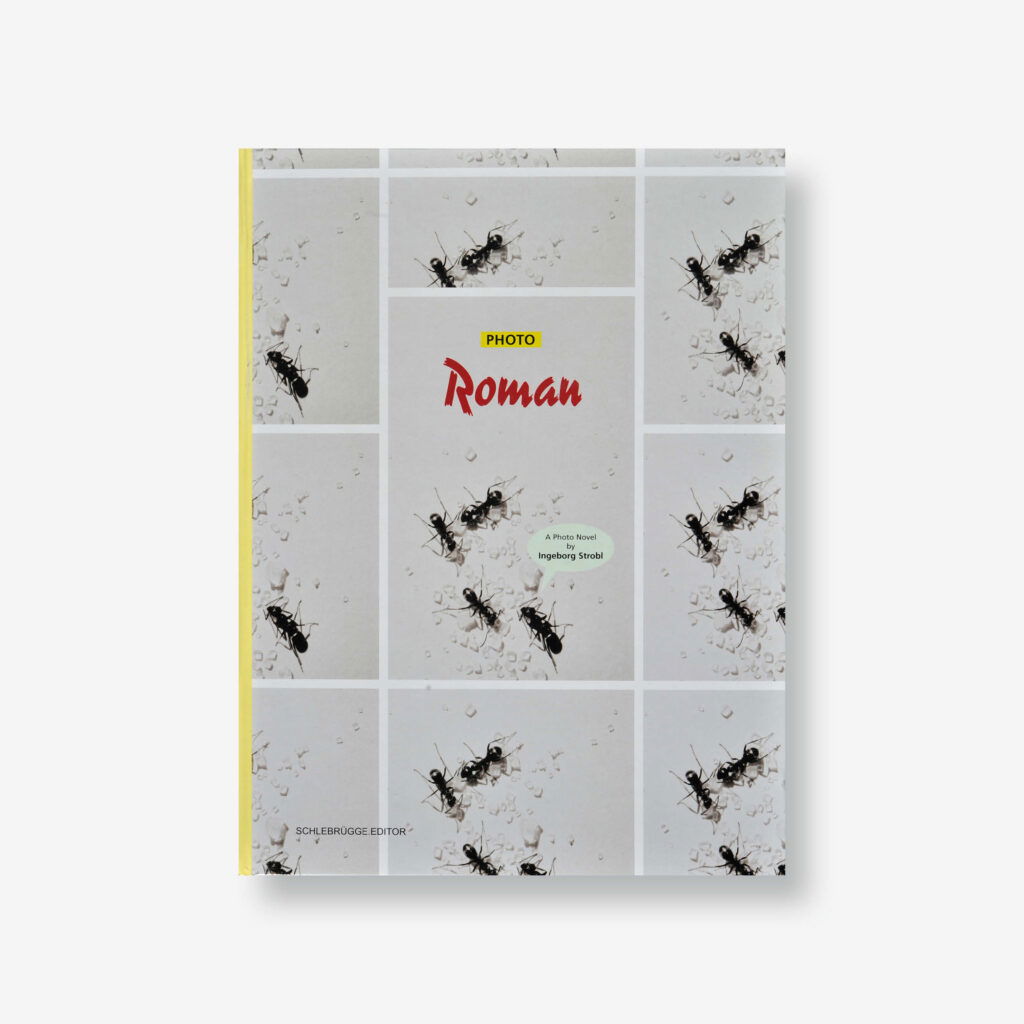

Ingeborg Strobl’s selection of works for the exhibition is determined primarily on the basis of diverging materiality, with content-related aspects seemingly of secondary importance. One particular focal point is the nature of the presentation, the display, the presence in the Fotohof’s gallery space. Self-exposed photographic paper corresponds with offset printing; miscellaneously framed photographic works, with video clips shown without sound on an old-fashioned monitor placed on the floor. The short videos feature observations made during her travels – everyday occurrences, random by nature. Unframed photographic works are placed on tables and inside display cases, including the oldest print found in her archives, a photo collage as a self-portrait, thought to date from 1970. Also test strips as relicts of time spent working in the darkroom, now associated with different contexts with the benefit of today’s point of view.

Decision and interpretation as two of the mainstays of photography are also reflected as defining characteristics in the use of the photographic material. From the Here and Now her gaze alights on the There and Then. It recalls the latter, recalibrates its perspective and, in doing so, determines memory in principle as an act of interpretation. (Rainer Fuchs)

In the exhibition Strobl combines individual photographs from different periods based not just on their different appearance and presentation forms (all the more enticing for being juxtaposed), but also on narrative criteria. Time and again her oeuvre features animals, mainly farm animals, pets and local fauna, an aspect reflected in the selection of press photographs.