Face to Face

Antoine d’Agata, Tina Bara, Valérie Belin, Clement Cooper, Bernhard Fuchs, Rince De Jong, Leo Kandl, Tomasz Kizny, Nina Korhonen, Anett Stuth, Mette Tronvoll

“Gegenüber – Menschenbilder in der Gegenwartsfotografie” is an exhibition project of the Landesgalerie am Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseum in Linz and FOTOHOF. As a result of joint research by both institutions, works by a total of eleven European photographic artists are being shown who deal with the direct representation of people.

The exhibitions taking place at the same time in the Landesgalerie Linz and the FOTOHOF present works by Antoine d’Agata (F), Tina Bara (D), Valérie Belin (F), Clement Cooper (GB), Bernhard Fuchs (A), Rince de Jong (NL), Leo Kandl (A), Tomasz Kizny (PL), Nina Korhonen (S), Anett Stuth (D) and Mette Tronvoll (N).

Alongside architecture and landscape, the examination of the portrait proves to be a focal point in contemporary photography. Each of the eleven positions presented pursues its own iconographic concern in dealing with an opposite. The exhibition project attempts to approach this phenomenon by analysing artistic concepts and approaches to the human image.

Engaging with the other is always also an exchange in the sense of reassuring people as parts of a social environment. What the artists have in common is an interest in engaging with the other as an engagement with themselves as well as with the society in which they live and work. Unconditional interest, analytical reflection as well as authentic personal involvement are just as characteristic as the fascination with the unbroken power of photography to put the world and time into the picture in an exemplary way.

The various artistic positions range from a factual documentary approach (Stuth, Fuchs, de Jong, Kizny) to a staged approach to the subjects (Bara, Belin), which can also explicitly include reflection on the photographic process (Tronvoll). Autobiographical approaches (Korhonen, Cooper) as well as the psychological moment in the interplay between photographer and model (Kandl) play an important role. The counterpart as an individual from a social group who is met with (racially motivated) rejection is the focus of interest in Antoine d’Agata’s new series.

Antoine d'Agata

“All photography is the authentication of presence.” The authenticity claim of photography formulated by Barthes has long since been undermined in its validity in times of manipulated, digitally processed images. In photography, the search for authenticity, objectivity and the documentation of reality has often been replaced by the question of the construction of reality, of fictionalisation and models of perception that are controlled by the omnipresence of media, often manipulated images, and that shape social identity. Photography is – and was even before the possibility of digital processing – always also interpretation. Nevertheless, there are renewed efforts in contemporary photography to address precisely the Barthesian immediacy of the human image and the associated aspirations to represent past reality. The majority of the works assembled in the exhibition convey these intentions very clearly. Of the artists represented, the French photographer Antoine d’Agata is the only one to show digitally processed photographs. Despite the use of digital montage techniques, the coherent representation of social reality in the south of France is the theme of his work. The starting point for the series “PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY”, which is being shown for the first time, was a building project by the city of Marseille to redesign a central district. D’Agata, who himself comes from Marseille, combines views of demolished buildings, city motorways and other characteristic urban motifs with portraits of young people attending a school in the affected district in digital adaptations. To accompany the images, he places quotations that relate more or less concretely to political and social problems in the city of Marseille. They come from politicians, journalists and influential representatives of the business world from historical as well as current media sources and give an idea of the manifold roots of racism. In most cases, the extreme political content of the quotes contrasts with the almost poetic links between the architectural situation and the figures of the young people.

Tina Bara

In the series “Matura”, Tina Bara portrayed a number of young girls in staged poses based on images taken from commercial advertising or fashion photography as well as artistic portrait photography. The choice of two pre-images was left to the girls. The photographs are accompanied by texts, which are, however, presented on separate panels next to the images. The relationship between image and text has gained importance in Tina Bara’s work in recent years. The texts give the sitters a voice, intensify the statement of the picture and at the same time illustrate an increasingly systematic-reflexive working method of the artist as well as her social and psychological interest in her counterpart. As in painting, the decision for a title in photography is already the decision to reveal additional information. In this respect, the title of the series “Matura” already gives an indication of the age and the specific life situation, marked by decisions and changes, in which the girls found themselves at the time of the photograph. These associations are confirmed by the girls’ texts, which contain personal thoughts and reflections on how they shape their lives, their wishful thinking and their identification with the respective media role models. On the threshold of adulthood and in search of stabilising their own identity, the young women in the photographic re-stagings are mostly oriented towards socially determined stereotypes that the depicted women represent. Yet staging and authenticity do not have to be mutually exclusive in Tina Bara’s work, which was determined from the beginning by an interest in the “mixing of reality and fiction, the depicted and the staged” as well as in the “dissolution of these apparent opposites”. Nor is the series to be seen primarily as a critique of mass-media identification factors and constructions of wishful thinking, i.e. as directed against the “wear-and-tear phenomena of media society” as in Richard Prince’s work, for example. Rather, Tina Bara’s work is to be seen as a sensitive examination of the phenomenon of individual identity formation, exemplified by a series of individual biographies of girls, and thus acquiring an overarching, collective significance. Images become “stand-ins and take on model character in relation to reality.” In doing so, she combines a psychological interest in documentation with a subjective-immediate access to her counterpart, the model. If we compare Bara’s works with those of Anett Stuth, we can see that they are two polar approaches to the same subject. While in Stuth’s work the naked young people are depicted completely in their own (physical) reality in their private surroundings, Bara’s productions offer the young girls the opportunity to create an ideal image of themselves. Nevertheless, both cases deal with questions of the construction of identity and the definition of self-image. In this context, Victor Burgin has pointed out the affinity with a phase of early childhood development studied by Jacques Lacan: in the so-called mirror stage between 16 and 18 months of life, the infant, who has hitherto experienced his body as fragmentary, recognises it as a whole in the mirror image: so here too there is a “correlation between the formation of identity and the formation of images”.

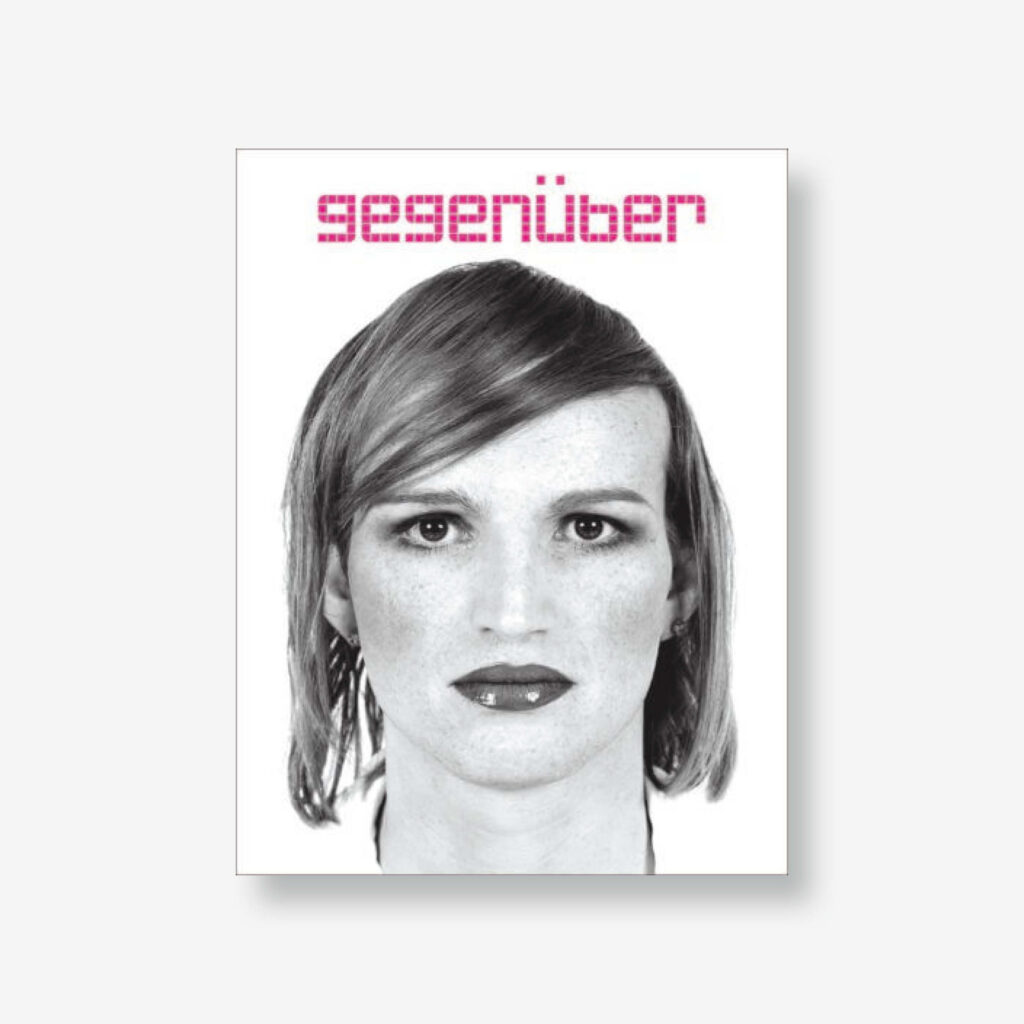

Valérie Belin

Valérie Belin captures the faces of transsexuals in large-format black and white photographs. The cropping is deliberately narrow and remains limited to the faces of the persons in a strict frontal view. The oversized proportions result in a feeling of monumentality, which, in combination with the high technical precision and the absolute renunciation of depth effect, creates the impression of the immediate presence of the image in space. The uncertainty about the portrayed person’s gender also causes a feeling of irritation in the viewer. The concept of the exhibition “Gegenüber” (Opposite) not only addresses the relationship between the photographer and the person photographed, but also that between the viewer and the image of the portrayed person, a component that is particularly effective in Belin’s works. The meaning of photography depends “solely on us, the recipients. We determine what form of life we breathe into the photograph. […] Basically, it can be said that in the end it is not really possible to tell from the photo itself what is real, what is posed, what is staged, what is voyeuristic and what is different from what really is or was. It always depends on us viewers to believe or distrust what is being commented on.” In an earlier series of photographs, Valérie Belin explored the accumulation of glass, mirror and crystalline objects, using black and white techniques and extreme light reflections to create almost abstract-looking compositions. Also due to the special use of light is the metallic sheen on the bodies of the “Bodybuilders”, which give an artificial object-like impression. This element of irritation, which is based on the fine line between naturalness and artificiality, between the lifeless and the living, also characterises the appearance of the sitters in the series of transsexuals, whose faces are characterised by mask-like features.

Clement Cooper

In several cases of the positions represented in the exhibition, one could recognise their own biographical context as the starting and connecting point of their artistic work (see Nina Korhonen, Bernhard Fuchs). In his photographic works, Clement Cooper combines personal consternation with an overriding socio-political concern. For him, the medium of photography is a “tool of cultural democracy” due to its general availability and easy accessibility. Growing up as the son of a white mother and a black father in a working-class area of Manchester, he experienced a specific form of racial discrimination as a child. His childhood was marked by the lack of clear ethnicity and the rejection he faced because of it; experiences that eventually triggered his project of portrait series of so-called “mixed-race people”. His photographs, produced in the classic black-and-white process, convey an authentic and self-evident approach to the genre of photographic portraiture, operating with the means of documentary photography. “I just photograph what is there. The way I approach a photograph is so simple. I use simple equipment, simple darkroom techniques. I don’t invent things. I don’t put things in. I don’t try to manipulate the subject-matter. It’s all in front of me. I didn’t create these things. They are there.” At the same time, Clement Cooper’s work is characterised by a high level of concentration and in-depth engagement with the subjects. Cooper worked for over three years on the series “Deep”, which consists of b/w portraits of mixed-race people from multicultural neighbourhoods of Liverpool, Bristol, Cardiff and Manchester. In order to build up a relationship of trust with the subjects, he lived and worked for several months in each of the cities concerned. Consequently, the photographs also convey an impression of the special characteristics of the urban landscape and the anonymous architecture of the housing estates built on the outskirts of English cities in the post-war decades.

Bernhard Fuchs

In full-body or three-quarter portraits, Bernhard Fuchs takes portraits of people in their immediate living environment. The photographs are carefully and harmoniously composed, but at the same time appear natural and not staged. In 1993, Bernhard Fuchs began studying photography with Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. It was the associated geographical change that made him look back at the inhabitants of his Mühlviertel origins, a look that gave rise to very sensitive portraits and was accompanied by a redefinition of his own identity. A special feature of the posture and the direct, open gaze of those portrayed, especially those from the rural environment, is a self-evident awareness of themselves, a certainty about their own identity that may never have been consciously reflected upon. Bernhard Fuchs wants to show much of the essence of the portrayed person and also of himself in the simplest possible way. By simultaneously addressing his own origins in the photographs, i.e. pursuing an authentic approach, he avoids a voyeuristic, constructed view of the “other”, in this case the rural population. Common clichés and traditional notions of “country life” and the concept of home are questioned in the sober photographs and the view is directed to the individual, to what is characteristic about the individual portrayed. His work oscillates between the depiction of social group membership and the focus on the individuality of the individual. For Bernhard Fuchs, the change from black and white to colour photography meant a liberation from the exclusive, existential concentration on the image of the human being to an increased inclusion of his surroundings. Accordingly, people are photographed in their natural surroundings, in their homes, at work or on the street, which supports the naturalness of their appearance. Although the background is deliberately reduced – often the people are merely standing in front of a simple house wall – it allows atmospheric conclusions to be drawn about the wider surroundings. Fuchs’ big-city portraits have a certain proximity to the works of Anett Stuth, who also takes portraits of average people characterised by objectivity in her ortlos series. Nevertheless, the approach, the relationship to the photographic counterpart in Bernhard Fuchs’ work is determined by more immediacy and familiarity. Stuth chose her models for the nude portraits through newspaper advertisements; the people in ortlos were strangers she approached on the street. In Fuchs’s case, on the other hand, the subjects are people from his immediate environment.

Rince de Jong

“Trying to get others to maintain their “natural” posture in front of the camera creates embarrassment: in this case, one cannot expect anything other than a feigned naturalness, in other words, a theatrical expression.” This process of posing and theatrical staging has characterised classical portrait photography from the beginning, usually bypassed only by snapshot photography. A special quality of Rince de Jong’s works, however, lies precisely in the fact that they are neither snapshots nor theatrical stagings. What she appreciated most about her models, Alzheimer’s patients in a nursing home, was the fact that they allowed themselves to be photographed without posing or putting themselves in the limelight. The unconscious renunciation of self-portrayal resulted in immediate, authentic image formulations. For even if the majority of the photographs suggest deliberately planned, elaborate stagings, most of the photographs were actually taken from everyday situations and were only slightly manipulated by Rince de Jong. For Rince de Jong, however, one of the most essential prerequisites of her work is the direct relationship she establishes with the people she portrays and with their everyday lives and surroundings. She had already been working as a caregiver in the home for eight years before the first photos were taken. A series of very sensitive photographs followed, mostly group portraits documenting everyday and special activities of the home’s residents. Any taint of voyeurism, pathos or dramatisation is excluded by the self-evident immediacy of the relationship between the photographer and the portrayed, as are pitiful connotations. Even though some of the photographs elicit a smile from the viewer, the dignity of those portrayed remains untouched. Overcoming distance and gaining trust and closeness to those portrayed is of elementary importance for the photographic work of Mette Tronvoll, Bernhard Fuchs and Clement Cooper as well as Rince de Jong. For the past two years, Rince de Jong has been working part-time as a caregiver for small children, to whom she will dedicate her next photo series.

Leo Kandl

For several decades now, Leo Kandl has continuously and consistently dealt with the genre of portrait photography by observing and recording people where their everyday life takes place outside their domestic environment. The varied form of the relationship between the photographer and his model play a significant role in most of the positions represented in the exhibition. Similar to Anett Stuth in her series “Suche” (Search), Leo Kandl also established contact with his “models” by means of newspaper advertisements. As expected, the terse call, which contained no information about the photographer and the context of the further use of the pictures, was primarily answered by younger, open-minded people from urban areas. In various urban centres, in London, New York, Vienna, but also in Havana, portraits were subsequently taken in public space, some of which look like snapshot-like street shots or private photographs. The models themselves determine their staging; clothing, pose, surroundings are chosen by them. The photographer acts in a very restrained manner, but still achieves an immediate expressive quality in the works. Kandl’s photographic method leaves room for emotional interactions, as the possibly risky approach of two unknown persons in the role play of model – photographer produces images that are characterised by curiosity and occasionally subtly erotically charged atmosphere. Going beyond the private, individual, however, universal things are also expressed. Statements about social affiliation and conscious constructions of individuality can be derived from various visual codes such as clothing, accessories or from the form of self-dramatisation. Kandl’s works combine a conceptual-documentary approach with an interest in the subjectivity and individuality of the sitter.

Tomasz Kizny

Tomasz Kizny has been working on an extensive series of portraits of underground passengers since 1998. During this time, he has taken around 1200 photographs of initially anonymous travellers in Berlin, Warsaw, Moscow and Paris. This year, he will add photographs in New York and Tokyo. His intention is to create a gallery of people at the turn of the millennium. Walker Evans, to whose Subway Portraits of the late 1930s Kizny refers, had taken his photographs with a hidden camera. Evans’ portraits are human images of an anonymous mass society in the USA in the period around the Second World War. However fleeting the encounter of photographer Tomasz Kizny with his fellow travellers, the name and job title of the person depicted is always a significant component of the photographs. This sociological dimension of the project is also the basis of Kizny’s second historically weighty reference, namely to August Sander’s “Antlitz der Zeit” (Face of Time), portraits systematised according to social groups from the time of the Weimar Republic. Evans’ and Sander’s works are not only milestones in the history of documentary photography, but also essential historically and politically relevant contemporary witnesses to the history of the USA and Germany respectively. In relation to this, Kizny’s work is less oriented towards the depiction of a specific place. It is not the description of the respective world above the underground tunnels in the different cities that is the focus of the photographer’s attention; his interest is a comparative one: he enables a comparison of the faces and the clothes, the gestures and the looks, the habitus that is perhaps different in each case. Tomasz Kizny’s pictures of people allow conclusions to be drawn about the different lives in the metropolises in whose underground the pictures are taken. The contemporary historical background against which Kizny’s work takes place is not only phenomena of the globalisation of the economy and politics, but above all the opening up of the former Eastern Bloc and the accompanying change in everyday cultures and lifestyles. “In the underground, people of different nationalities, professions and social positions meet each other. It is a moving portrait gallery. The choice of this location has a metaphorical meaning. The passengers mentioned in the title travel from station to station, between what was and what is to come, between history and the future,” says Kizny about his work.

Nina Korhonen

Memory is an important element in Nina Korhonen’s artistic practice. For her first book project, she recreated scenes from her own childhood with the help of two teenage actresses. In very coherent black-and-white photographs, the artist attempts to conjure up the magic of a place that serves as a stage for recognising oneself, albeit with a time delay, in the other person. This autobiographically motivated search for traces will also be the determining factor in her next project. This time it is her grandfather’s family album that forms the beginning of a picture story about a person close to her from the family circle, namely her grandmother Anna. Based on the found, colourful snapshots of her grandfather, she develops her own story from the world of the “American way of life”, in the centre of which is her grandmother, who emigrated to the United States of America in 1959. From 1994 to 1999, the last years of her grandmother’s life, Nina Korhonen worked on her cycle “ANNA”. This is about the realisation of her grandmother’s long-held wish to spend the second half of her life in the USA. At the age of over forty, after her own family had been taken care of in Finland, she succeeds in fulfilling this wish and settles in Finntown in Brooklyn. As a housekeeper for a wealthy family in Manhattan, she also participates in America’s economic success during a prosperous time, to the point of buying a small house in Florida. When Nina Korhonen decides to travel to the USA and accompany her grandmother for a longer period of time with her camera, she is shown a self-confident woman of almost eighty who “is still a beautiful, strong and sensual person” (Korhonen). The images that emerge are characterised by the closeness and trust of the subject, who both allows insights into very intimate moments of life and does not shy away from capturing public everyday situations. In brilliant, large-format colour photographs, a dialogue between two women from different generations unfolds and finds expression in a multi-part series of images that is not only shaped by a shared family history (Korhonen also left her Finnish homeland a good twenty years ago and has lived in Sweden ever since), but also by the photographer’s gender-specific way of seeing and her search for identity. The grandmother’s often almost astounding, body-emphasising self-portrayal testifies to a sensuality that is retained with dignity into old age. The grandmother’s appearance in public space, while shopping, but also in encounters with friends, exemplifies how cultural Anna is also drawn in her personal environment in the sense of a psychologising portrait, while in public she blends into the iconography of her new home in a somewhat more distanced form. Through such an interplay, Nina Korhonen thus succeeds in interweaving individual and general life stories.

Anett Stuth

Looking at the depiction of different phases of life in current artistic portrait photography, as reflected in the works in the exhibition, one can see a particular interest in age stages that are usually marked by decisive changes. Phases that are generally regarded as psychologically significant for the identity of the individual, such as childhood, puberty, pregnancy / motherhood, and the like, thus become the pictorial theme. In line with the socio-politically virulent problem of the ageing of the Western population, the theme of ageing has been added in recent years as a starting point for photographic exploration. In the photo series “Suche” (Search) (2000), Anett Stuth focuses on the aforementioned transitional phase of uncertainty and the search for identity of young people on the threshold of adulthood. Stuth found her subject by means of newspaper advertisements in which she sought young people for nude photographs. The nakedness of the portrayed reinforces the impression of a certain disorientation and fragility by depriving them of any possibility of at least superficially constructing their identity. The few fragments of their private living environment that are depicted allow a conclusion to be drawn about their social background, but offer little support to those portrayed. Facial expressions and body posture suggest sensitivities and feelings between unstable insecurity and self-confident youthful determination. In the 1996 series “Ortlos”, Stuth’s diploma thesis at the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, the artist cast her gaze on people of a middle age, which is usually not predestined for life-defining changes. The inconspicuous averageness of the appearance of the people photographed actually suggests a certain monotony in their living conditions. The people are photographed in front of anonymous urban architectural situations, which are also characterised by uniformity and mediocrity. The series also includes still-life-like interior photographs of the private living situation of the people portrayed. There are sometimes strange parallels in form and colour between the people’s clothing and the architecture that surrounds them. Nevertheless, even these people do not lack a certain insecurity in their appearance, which could have something to do with the political situation in East Germany. Especially this middle generation, who had spent most of their lives in the GDR, found it particularly difficult to find their way within a drastically changed living environment after the political turnaround. Similar to Mette Tronvoll’s work, this subjective approach to the people portrayed, which conveys a high degree of authenticity, stands in tense contrast to a factually neutral, almost documentary-conceptual form of the photographs, which in both cases reveal an affinity with German portrait photography of the last decades (Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff). The photographic work of Timm Rautert, whose master class Anett Stuth attended at the Leipzig University of Applied Sciences, is also characterised by precise objectivity and documentary observation.

Mette Tronvoll

The work “Double Portraits” is a series of diptychs, each consisting of two photographs of the same person. In Tronvoll’s New York studio, about 40 photographs of a person were taken in daylight, from which the artist selected two. Although or precisely because they show only minimal differences, they evoke in the viewer an immediate concentration on comparative perception. Fine variations and nuances in the posture and facial expression of the portrayed can be discerned. The neutral background, which only changes slightly due to the incidence of light, the simple clothing and the almost emotionless facial expression of the sitters lend the photographs a factual, documentary character. The process of shooting in the double portraits has a certain affinity with the creation of the earliest portrait photographs in that at that time the models often had to remain in one and the same pose for hours. When comparing the two pictures, one thinks that in some cases one can indeed detect a latent fatigue in gaze and posture, but above all certain difficulties in maintaining the chosen pose. The pose corresponds to the image that the sitter wants to leave of himself, but which can only work for the moment. It is precisely this decisive moment, usually a determinant of photography, that Mette Tronvoll attempts to undermine by adding a second image. Although created in the medium of traditional studio photography, her works thus gain a cinematic quality by appearing like two stills from the same scene. “The pose is eliminated and denied by the uninterrupted succession of images.” In a sense, Tronvoll questions this – according to Barthes – elementary difference between photography and film in the “Double Portraits”. At the same time, Tronvoll’s works – and this applies to the Double Portraits in particular – are “an exchange between looking at and being looked at”. The exhibition “Gegenüber” thematises this exchange, which on the one hand presupposes a relationship of whatever kind between the photographer and the portrayed, but on the other hand also means the relationship between the viewer and the portrayed, in various possible variations. The question of closeness or distance to the portrayed is important in a large part of the exhibited works. For a long time, Mette Tronvoll had worked exclusively in the studio with acquaintances and friends. When she worked with strangers for the first time for the series “Isortoq Unartoq”, which was created in Greenland, this work was preceded by an intensive study of the people and their extreme living conditions. The series of double portraits also includes a self-portrait of the artist. However, while the self-portrait in contemporary photography functions primarily as a means of artistic self-dramatisation, in Mette Tronvoll’s work it appears succinctly as part of a series without occupying a special position within it.