Oswald Wiener

Oswald Wiener

When the writer Oswald Wiener moved to Dawson City in Canada with his wife Ingrid in 1984, it was another act in his quest for knowledge. In another context, one would speak of how he and his wife Ingrid thereby explored the boundaries of art and life. He himself thought he had left art behind after the epoch-making work “the improvement of central europe, novel“¹. His first expeditions to Iceland at the end of the 1970s and his move to the Canadian wilderness were part of this, a strong statement away from the conventional, albeit “avant-garde“ cultural establishment, in the clear awareness that he could not escape it anyway. Apart from the burning interest in the extremes of nature and climate near the Arctic Circle, in extraordinary civilisational and social circumstances in an unusually prominent historical context, this experiment served to shift and expand the boundaries of one’s own actions, or to examine them again and again. The Arctic tundra and the subarctic forests became the setting for an experiment in living on the edge of a now global culture. Dawson City was predestined for this. In this environment, the living and working environments, a house in the forest, the claims café they ran – a restaurant with Wiener schnitzel and apple strudel and the only Italian espresso machine on a territory the size of the Federal Republic of Germany – became sites of introspection and thus of a practice of thinking beyond art, science and philosophy.

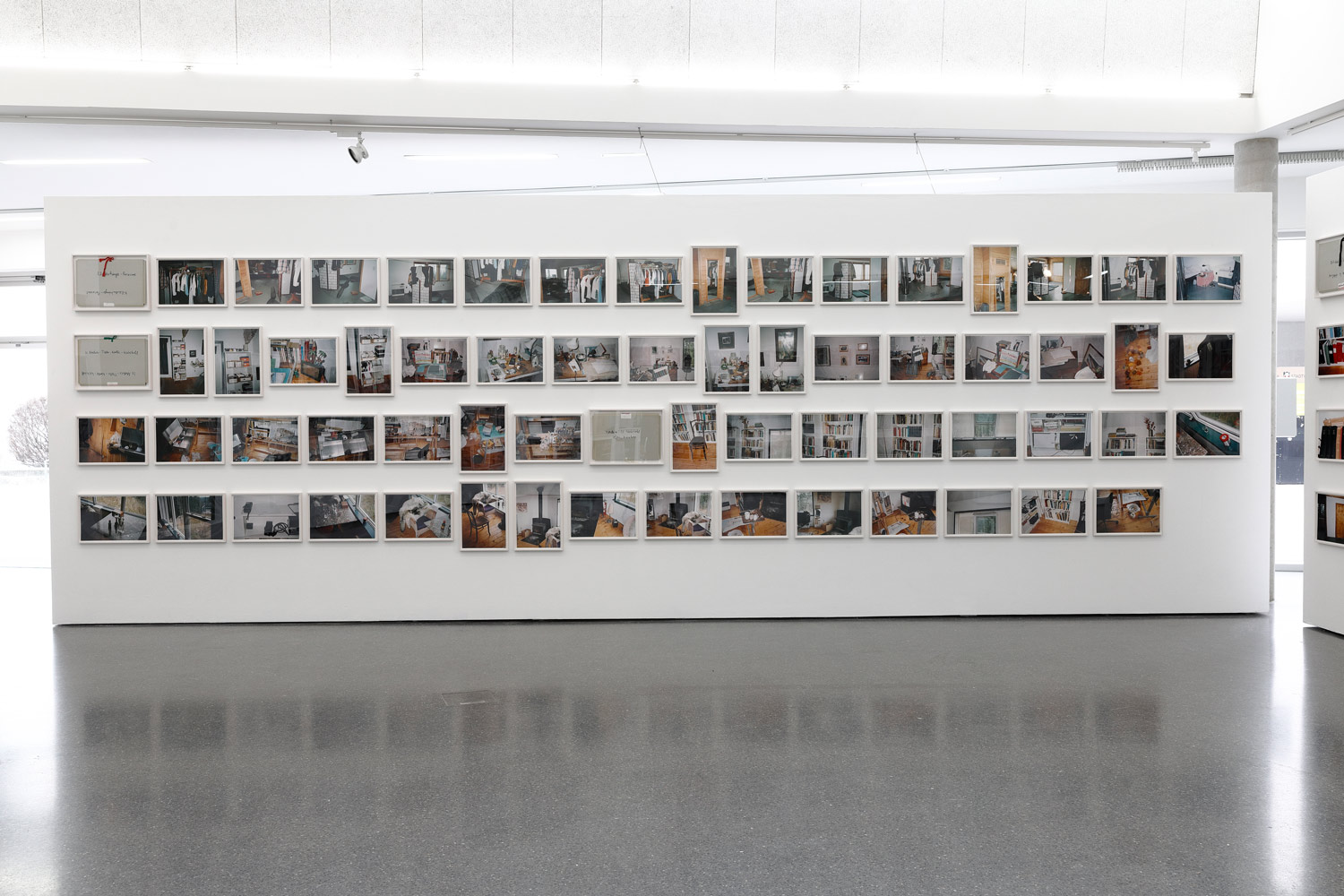

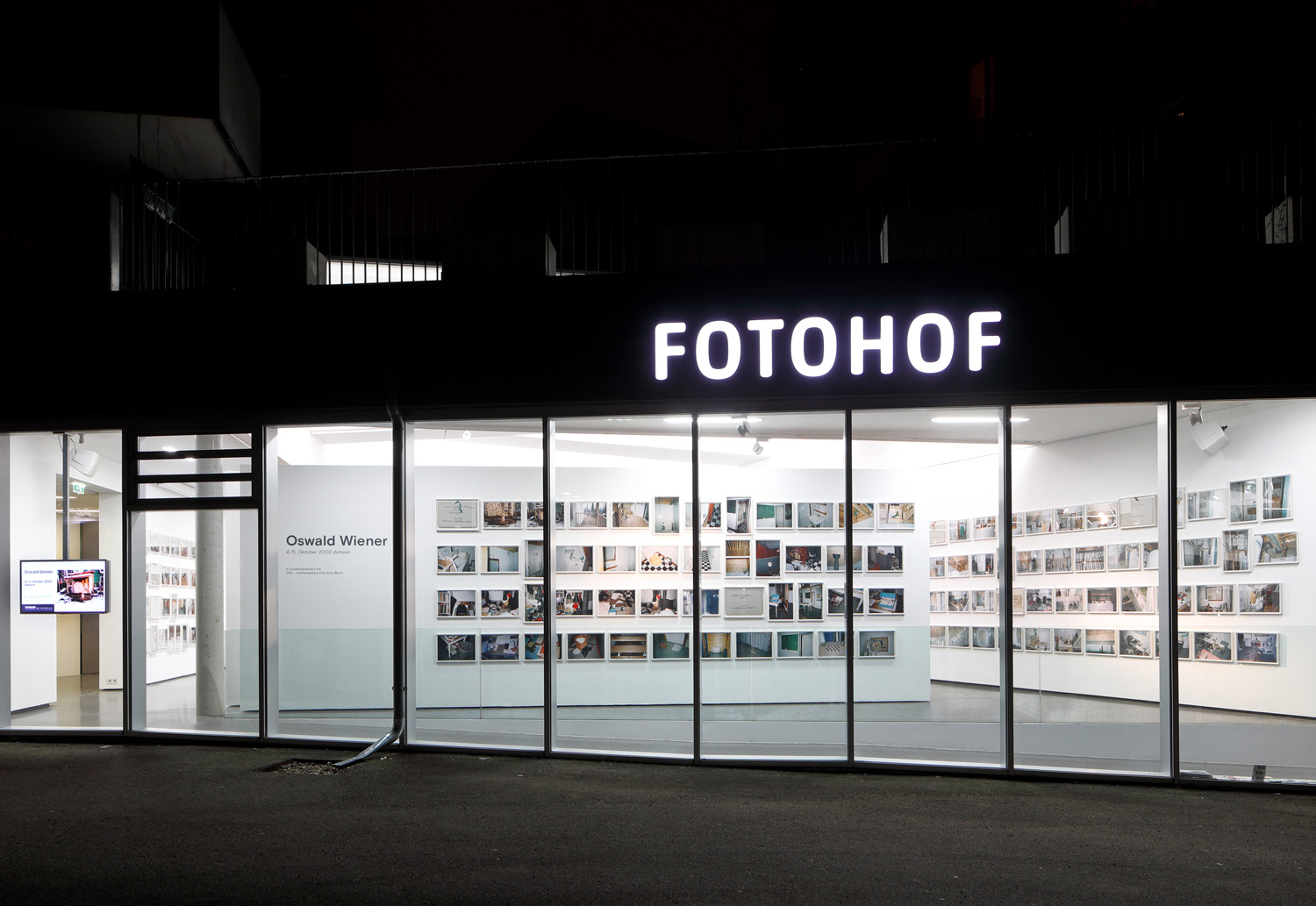

As their long stay drew to a close in the early 2000s, the times they spent in Europe became longer and longer, and their interests shifted once again, the need to depict the innermost place of their work and long refexions obviously arose. The house was captured in detail from the inside, and rather sparsely on the outside, in more than 300 photographs, thus surveying it as it were. It shows the couple’s everyday living and working environment, Ingrid’s loom is just as much a part of it as Oswald’s books and their records. But the pictures go far beyond this and can be read as a document of a space of thought and perception – as a world for itself in its factual validity. Thus we may understand this undertaking in a series of attempts to grasp consciousness spatially and thus to give reflection a very personal place. This is a consideration of the present compendium of photographs from the outside – first of all, even without going into detail about Wiener’s philosophy of thought – as an artistic phenomenon. A posthumous contemplation, to which he gives rise in his handling of these photos. This documentation consists of prints that Oswald Wiener made during his lifetime, which he exhibited and which were subjected to an order. Individual photos were also given away – as his works of art, as it were – on special occasions. So it makes perfect sense to posthumously present them in a comprehensive exhibition and thus bring them into a larger context – both in art history and intellectual history, as well as in Wiener’s linguistic and intellectual oeuvre. It should not be concealed that Wiener also saw it differently when he exhibited the photographs in a Viennese art gallery², as quoted in a text he wrote for this show:

“I do not claim any art status for these photographs. If they are to go beyond suggestions for the spatial and temporal reconstruction of an anonymous situation – which may already suffice as a reason for existence – they have been for a certain interest in my person and that of my wife. Their status of innocent snapshots does not derive from an artist’s pose; the blurriness and apparent awkwardness are appropriate, as these images contain a great deal of unmanipulated information and discretion is desired.“³

This contradiction will be investigated. But it is also symptomatic of much that led Wiener into the border areas of his interests. His distrust was directed at the constructions of disciplines and fields such as literature or art, as well as society in general, science or philosophy. As symptomatic as such an attitude is for Wiener’s thinking, it also pervades the self-image of many protagonists of modernism who venture into such extremes. Thus, in Kurt Schwitters’ “Merz Bau“ (ca. 1923), we can probably see a comparable attempt to make the space of thought visible and comprehensible, as in Bruce Nauman’s “Mapping the Studio“ (2001) as a reflection of creative activity, likewise generated from a studio in a place of retreat in a scenic wilderness. In this sense, the exhibition of the entire photographs of this place will be accompanied by a publication that will situate this endeavour in Wiener’s thinking in terms of art and the humanities and, in addition to the curator, will also allow important intellectual companions of Wiener to have their say. (Peter Pakesch, Lichtenberg, April 2022)

¹ Oswald Wiener, die verbesserung von mitteleuropa, novel, Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbeck bei Hamburg, 1969

² Oswald Wiener, 4/5 October 2003 at home. Galerie Charim, Vienna 2004, http://www.kunstnet.at/charim/04_05_12.html

³ Quoted from http://www.kunstnet.at/charim/04_05_12.html